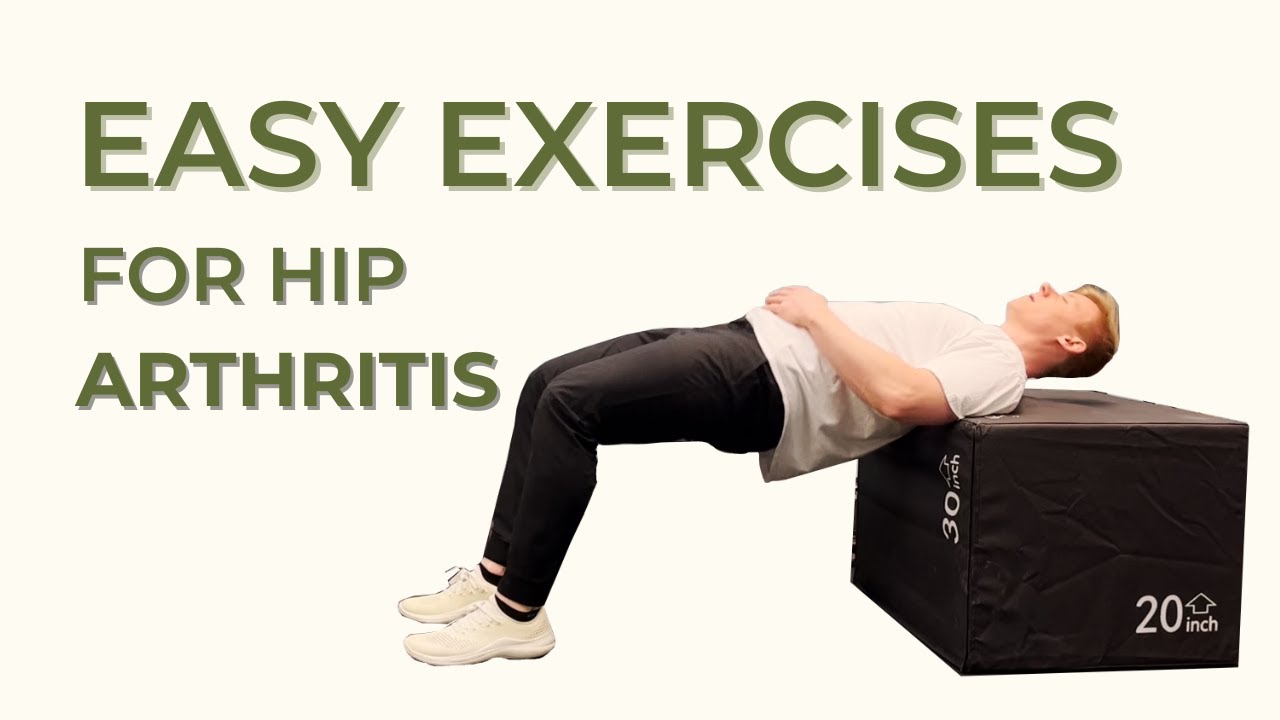

How to exercise with osteoarthritis!

In the last article I about how the guidelines only strongly recommend exercise and education for everyone as well as weight loss for those who are obese1-3. That’s cool, but just saying that exercise is helpful is quite vague and can leave a lot of people wondering what to do. For this article I will be discussing what the evidence has to say about what types of exercise are safe (spoiler they all are), and how much should be done.

Since the idea of wear and tear is still a lingering belief, I want to reiterate that this belief is incorrect4,5. The belief may cause some people to avoid exercise since they think that it will damage their joints; however, it has been shown many times that strength training does not decrease the amount of cartilage you have in your joints if you have osteoarthritis, increase the amount of defect in your cartilage, or increase the amount of inflammation in your joints6-8. There also may be some concern around running since it is often seen as high impact and potentially that may be harmful to your joints, but yet again the evidence shows that running, as well as walking programs, are completely safe for your joints and do not increase the progression of osteoarthritis9,10. Furthermore, there is a potentially protective effect of exercise on cartilage in healthy individuals, meaning that if you exercise at a high enough intensity your body may actually increase the amount of cartilage present in your joints11. Awesome, now you can politely tell someone to shut up if they ever say that you can’t do something because of arthritis.

Now that we have cleared the air and shown that exercise is safe for your joints, what kinds of exercise should be done? Programs that used what the Canadian and american guidelines recommend for physical activity for healthy adults (150 min of moderate-vigorous aerobic activity and muscle strengthening activities 2x or more per week strengthening all major muscle groups)1,2 have been shown to be effective in reducing pain and disability while also building strength in those with osteoarthritis12,13; however, when looking at just pain and disability, they didn’t cause greater improvements when compared to programs that didn’t match those recommendations12. A couple important things that were found were a minimum of 30% strength gain in the lower limbs was likely to produce a decrease in pain, and 40% was likely to show a decrease in disability12. This shows that if you don’t reach the guideline recommendation you can still get similar outcomes as long as you are building enough strength!

Ok following those guidelines is a good start, but can we get a little bit more specific in terms of recommendations? What if someone is already presenting with high or low strength, does tailoring the program based off of those characteristics help? Sadly, or happily, no. Tailored programs that are based off of how you present are not found to be more helpful than just following general exercise recommendations14. If you already have high strength then you still benefit from becoming even more jacked and stacked, YEAH BUDDY!

So you can do pretty much anything that you want as long as you are focusing on increasing your strength and you can use the guidelines to help direct how many times a week you are exercising. This is great but you still are left in the dark somewhat when it comes to actually working out. You are probably wondering how many sets and reps you should be doing as well as how long do you have to workout for? To start with how long you have to workout for, it is for life. The longer the programs are for exercise, the longer the benefits last for, and when comparing actual numbers programs that were 50-53 weeks long outperformed all of the shorter ones15. This makes sense since humans are dynamic organisms that are constantly adapting, so if you stop exercising, you are going to lose those adaptations. The optimal dose for sets and reps is unknown when it comes to osteoarthritis3,13, but for healthy adults it seems to be around 2-3 sets of 7-9 reps per exercise with at least 70% of your 1 rep max15.

So summing everything up, if you work out 2-3 times per week doing 2-3 sets of 7-9 reps for all of your major muscle groups, as well as getting 150 minutes/week of walking and/or running in, you are going to make some serious gains and decrease pain and disability! All exercise is safe and does not cause harm to your joints so there is no need to be afraid!

As always, it’s time to get out there and move!

*This is an informational resource and not medical advice, please consult your healthcare practitioner for diagnosis, treatment, and guidance.

References

- https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/adults-65/

- Young JJ, Važić O, Cregg AC. Management of knee and hip osteoarthritis: an opportunity for the Canadian chiropractic profession. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2021 Apr;65(1):6-13. PMID: 34035537; PMCID: PMC8128331.

- Man GS, Mologhianu G. Osteoarthritis pathogenesis - a complex process that involves the entire joint. J Med Life. 2014 Mar 15;7(1):37-41. Epub 2014 Mar 25. PMID: 24653755; PMCID: PMC3956093.

- Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Feb 9;325(6):568-578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22171. PMID: 33560326; PMCID: PMC8225295.

- Bricca A, Juhl CB, Steultjens M, Wirth W, Roos EM. Impact of exercise on articular cartilage in people at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Aug;53(15):940-947. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098661. Epub 2018 Jun 22. PMID: 29934429.

- Bricca A, Struglics A, Larsson S, Steultjens M, Juhl CB, Roos EM. Impact of Exercise Therapy on Molecular Biomarkers Related to Cartilage and Inflammation in Individuals at Risk of, or With Established, Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Nov;71(11):1504-1515. doi: 10.1002/acr.23786. PMID: 30320965.

- Van Ginckel A, Hall M, Dobson F, Calders P. Effects of long-term exercise therapy on knee joint structure in people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Jun;48(6):941-949. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.014. Epub 2018 Oct 16. PMID: 30392703.

- Lo GH, Musa SM, Driban JB, Kriska AM, McAlindon TE, Souza RB, Petersen NJ, Storti KL, Eaton CB, Hochberg MC, Jackson RD, Kwoh CK, Nevitt MC, Suarez-Almazor ME. Running does not increase symptoms or structural progression in people with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Sep;37(9):2497-2504. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4121-3. Epub 2018 May 4. PMID: 29728929; PMCID: PMC6095814.

- Lo GH, Vinod S, Richard MJ, Harkey MS, McAlindon TE, Kriska AM, Rockette-Wagner B, Eaton CB, Hochberg MC, Jackson RD, Kwoh CK, Nevitt MC, Driban JB. Association Between Walking for Exercise and Symptomatic and Structural Progression in Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Jun 8. doi: 10.1002/art.42241. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35673832.

- Grzelak P, Domzalski M, Majos A, Podgórski M, Stefanczyk L, Krochmalski M, Polguj M. Thickening of the knee joint cartilage in elite weightlifters as a potential adaptation mechanism. Clin Anat. 2014 Sep;27(6):920-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22393. Epub 2014 Mar 20. PMID: 24648385.

- Bartholdy C, Juhl C, Christensen R, Lund H, Zhang W, Henriksen M. The role of muscle strengthening in exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017 Aug;47(1):9-21. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 Mar 18. PMID: 28438380.

- Moseng T, Dagfinrud H, Smedslund G, Østerås N. The importance of dose in land-based supervised exercise for people with hip osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Oct;25(10):1563-1576. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.06.004. Epub 2017 Jun 23. Erratum in: Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018 Mar 14;: PMID: 28648741.

- Knoop J, Dekker J, van Dongen JM, van der Leeden M, de Rooij M, Peter WF, de Joode W, van Bodegom-Vos L, Lopuhaä N, Bennell KL, Lems WF, van der Esch M, Vliet Vlieland TP, Ostelo RW. Stratified exercise therapy does not improve outcomes compared with usual exercise therapy in people with knee osteoarthritis (OCTOPuS study): a cluster randomised trial. J Physiother. 2022 Jun 24:S1836-9553(22)00055-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2022.06.005. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35760724.

- Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015 Dec;45(12):1693-720. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9. PMID: 26420238; PMCID: PMC4656698.

Member discussion